Ursonate by Kurt Schwitters

Kurt Schwitters, 1887-1948

The Ursonate or

Sonata in Primal Sounds

Fümms bö wö tee zee Uu

pögiff,

kwii Ee.

These are the first lines of the Kurt Schwitters Ursonate, or sonata in primal sounds. This forty-minute phonetic poem is one of the legends of Dadaism, an artistic movement that arose in Zurich during the First World War and thereafter spread rapidly, especially in Germany and France.

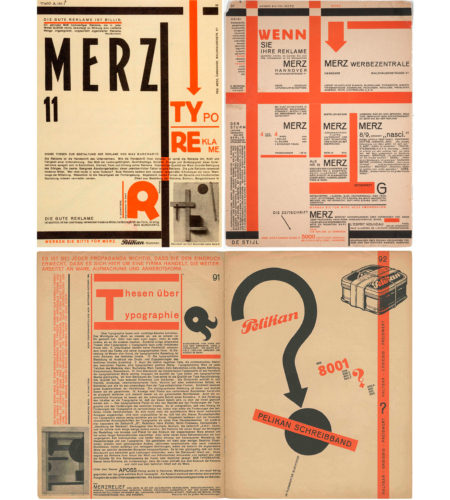

The Dadaists were a loose collection of artists united only but by their anti-bourgeois, anti-naturalistic tendencies. Kurt Schwitters, who formed his own Dada group in the provincial city of Hanover in 1919, is best known for his collages which use the debris of the commercial world, such as ticket stubs, newspaper advertisements, nails, corks, and wire, to construct fanciful assemblages of shapes, colors, and juxtaposed meanings. He coined the term “Merz”, a syllable he extracted on impulse from the word “Kommerzbank” (bank of commerce), to apply to all his artistic work, as well to the art review he published from 1923 to 1932.

Unlike the Berlin Dadaists who were more politically revolutionary, even nihilistic in their aims, Schwitters was something of a Romantic idealist with a firm belief in the value of art, even if its significance eluded him.

In 1921 he wrote in Merz: “Art is a primordial concept, exalted as the godhead, inexplicable as life, indefinable and without purpose. The work comes into being through artistic evaluation of its elements. I know only how I make it, I know only my medium, of which I partake, to what end I know not.”

For Schwitters the medium was incidental, since any materials could be shaped by an artist’s hand. Not surprisingly Schwitters branched out into sculpture and, like many other Dadaists, took a great interest in language as well. His own poetry, initially influenced by the expressionist verse of August Stramm (1874-1915), grew to include Dadaist experiments in nonsense verse, wordplay, graphic poetry, phonetic poems and sound-collages similar to those by the Berlin Dadaist Hugo Ball, Raoul Hausmann, and Richard Huelsenbeck. Schwitters described poetry simply as letters, syllables, words, and sentences. “Meaning is important,” he wrote, “only if it is employed as one such factor.”

Schwitters’ own comments: “The Sonata consists of four movements, of an overture and a finale, and seventhly, of a cadenza in the fourth movement.

The first movement is a rondo with four main themes, designated as such in the text of the Sonata. You yourself will certainly feel the rhythm, slack or strong, high or low, taut or loose. To explain in detail the variations and compositions of the themes would be tiresome in the end and detrimental to the pleasure of reading and listening, and after all I’m not a professor.”

“In the first movement I draw your attention to the word for word repeats of the themes before each variation, to the explosive beginning of the first movement, to the pure lyricism of the sung “Jüü-Kaa,” to the military severity of the rhythm of the quite masculine third theme next to the fourth theme which is tremulous and mild as a lamb, and lastly to the accusing finale of the first movement, with the question “tää?”…”The fourth movement, long-running and quick, comes as a good exercise for the reader’s lungs, in particular because the endless repeats, if they are not to seem too uniform, require the voice to be seriously raised most of the time.

In the finale I draw your attention to the deliberate return of the alphabet up to a. You feel it coming and expect the a impatiently. But twice over it stops painfully on the b…”

“I do no more than offer a possibility for a solo voice with maybe not much imagination. I myself give a different cadenza each time and, since I recite it entirely by heart, I thereby get the cadenza to produce a very lively effect, forming a sharp contrast with the rest of the Sonata which is quite rigid. There.””The letters applied are to be pronounced as in German. A single vowel sound is short… Letters, of course, give only a rather incomplete score of the spoken sonata. As with any printed music, many interpretations are possible. As with any other reading, correct reading requires the use of imagination. The reader himself has to work seriously to become a genuine reader. Thus, it is work rather than questions or mindless criticism which will improve the reader’s receptive capacities. The right of criticism is reserved to those who have achieved a full understanding.

Listening to the sonata is better than reading it. This is why I like to perform my sonata in public.”

In my mind, Schwitters comments the Second Viennese School, the Twelwe tone system through Romantic tradition of form; there is rhythm but no clear pitches or tones. I find Schwitters’ fantastic and renewing compared to formulaic use of Serial compostition technique.

Timo Korhonen

June 29, 2018 @ 4:28 pm

Thank you for the great article

August 15, 2018 @ 6:09 pm

Thanks, it is quite informative